One of the challenges—and joys—of genealogy is learning to live in the space between certainty and educated guesswork. We all want documented proof, but sometimes the evidence comes in layers: parish records, census entries, occupational patterns, naming conventions, and now, DNA.

My 4th great-grandfather, James Copeman, is a perfect example of that puzzle in progress.

James was born in 1814 in Beccles, Suffolk, England. In 1854, he immigrated to the United States and eventually settled near the Iowa–Minnesota border, not far from where I was born generations later. My grandmother’s maiden name is Copeman, which made this branch of the tree especially interesting to me from the start.

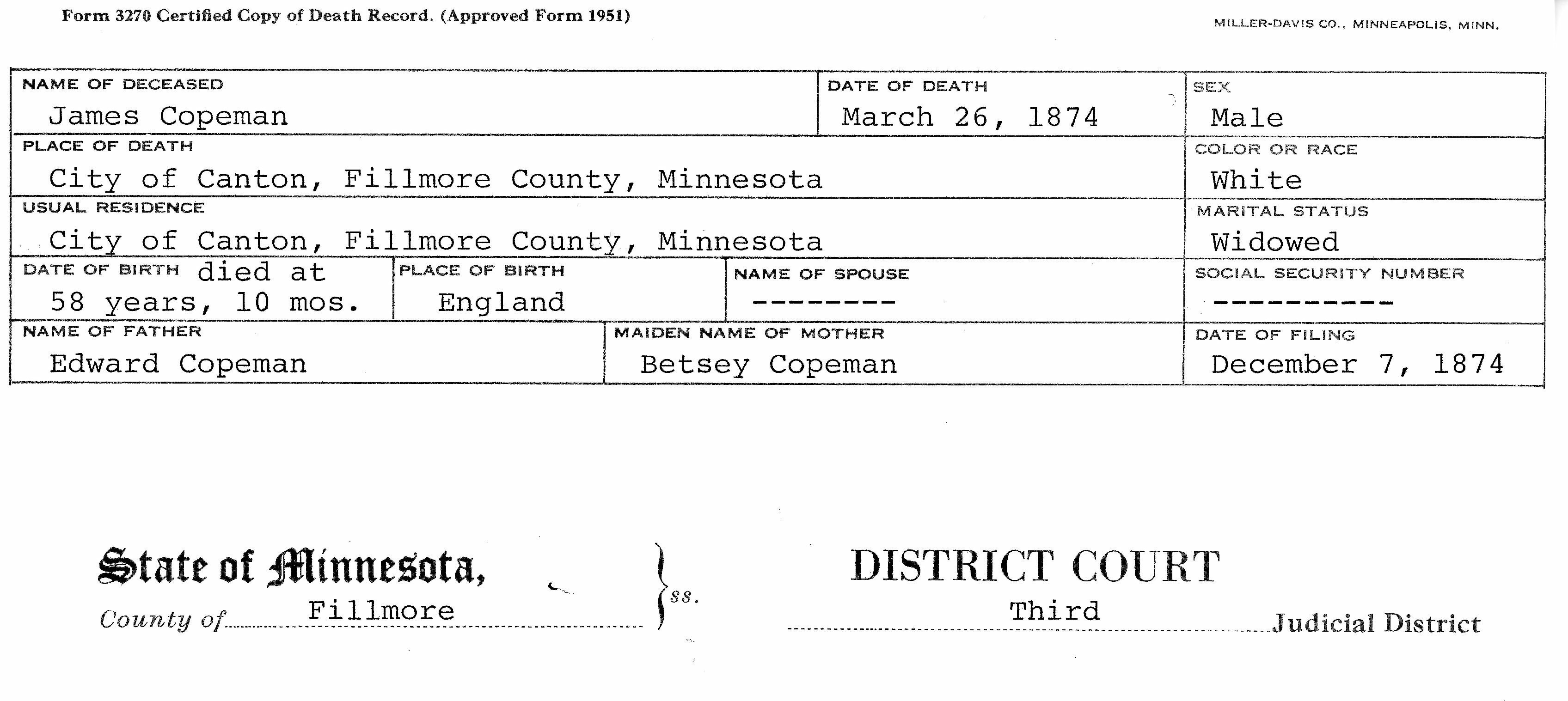

But like many researchers know, records before immigration can be frustratingly sparse. James’s death certificate listed his parents as Edward Copeman and “Betsey”—with no maiden name and no clear links to a traceable family. For a long time, that’s where the trail ended.

Until I started digging deeper.

The Copeman Family of Beccles

Using parish church records available through Ancestry.com (if only they had referral links!), I reviewed baptisms in Beccles from the late 1700s through the early 1800s. I found just one Edward Copeman in that area at that time—married to a Lorina Crickmore. Together, they had nine known children between 1798 and 1823, well documented in the church registers.

James doesn’t appear in the baptism records—but the timeline tells an interesting story.

Edward and Lorina’s earlier children were all baptized within a month of birth, but after 1812, there’s a noticeable gap. Their next child wasn’t born until 1817—leaving room for James, born in 1814, to plausibly fit right in. What’s more, the last three children—Elizabeth (b. 1817), Harriet (b. 1818), and Mary Ann (b. 1823)—were baptized unusually late. Elizabeth and Harriet weren’t baptized until 1823, and Mary Ann not until 1831. That shift in behavior makes it much easier to believe that James simply slipped through the cracks—or never had a baptismal record created or preserved.

It’s also worth noting that Edward and Lorina named one of their daughters Lorina, and James later married a woman named Lorena. It seems to have been a popular name in that region at the time, but the repetition is still notable.

Supporting Clues

Other clues add weight to the theory.

Census records show that James lived near other Copemans throughout his life in England—presumed siblings from the Edward and Lorina family. His occupation was a baker, which was also a family trade. One of his sons in the U.S. became a gardener—again, a shared family occupation. These details may seem small, but they align neatly with what we know about the rest of the family group.

James’s emigration always raised questions for me. Why would he be the only one to leave, if he truly was Edward and Lorina’s son? But that piece clicked into place once I researched his wife. Lorena Jones had multiple siblings who emigrated around the same time. James and Lorena followed that migration path, moving alongside her family across the U.S. So it’s likely that James didn’t leave England because of his own family—he left for hers.

DNA Evidence

Of course, circumstantial evidence is only part of the story. Now we have DNA.

My grandmother—a direct Copeman descendant and now 88 years old—agreed to take a DNA test. She currently has over 20 confirmed DNA matches who descend from five different children of Edward and Lorina Copeman. She also has 50+ matches who descend from James himself, which is expected. These matches are consistent and fall where they should if James is indeed part of this family.

The Copeman surname wasn’t common in Suffolk during the early 1800s, which also helps. There were some Copeman lines in nearby Norfolk, and we do have a few matches to cousins from those families—leading me to believe Edward or his father may have originated there before settling in Beccles.

If you’re exploring your own family mysteries and haven’t tried DNA testing yet, it’s worth considering. I use AncestryDNA, which has a huge match database and helpful family tree tools. You’ll save 15% per kit using my referral link, and if you use it, I receive a small thank-you in the form of a $10 Amazon gift card. Win-win.

Why I’m Sharing This

This isn’t the conclusion of a mystery—it’s an open case file with a well-supported theory. I’m sharing it both to document the path I’ve taken and to hopefully connect with others researching the Copeman line, whether in Suffolk, Norfolk, or across the ocean.

Genealogy isn’t always about certainty. Sometimes it’s about collecting clues, weighing patterns, and following the story as far as it will take you.

And in this case, the story points clearly to Edward Copeman and Lorina Crickmore as the likely parents of James Copeman.

If there’s a lesson in this process, it’s this: Ask questions while you still can. Talk to the older family members. Record their stories. And if you’re using DNA as a research tool, don’t wait—test the oldest generation available. Each generation dilutes what you can detect through shared matches, and those small segments that link us to cousins two hundred years ago get harder and harder to trace with each passing decade.

Because while the paper trail can fade, the stories—and the DNA—are still out there, waiting to connect us.