When I first started genealogy, I was young, newly married, and eager to make discoveries. My husband, nearly thirty years older, was already deep into family history, and I threw myself into it with equal enthusiasm. But back then, I approached genealogy like a collector: gathering names, dates, and tidy little facts.

One of the first stories I proudly wrote down was about James and Lorena Copeman, my ancestors who immigrated from England to the United States. I recorded that they “came to America leaving five of their fourteen children behind.” I thought it sounded dramatic, even poignant.

But years later, with more experience — and perhaps more life lived — I realized how wrong I had been. They didn’t leave five children behind. They buried them. Five of their children died as infants. What I had reduced to a statistic was actually a story of grief, resilience, and parents who carried unthinkable loss across an ocean.

Learning to See What’s Missing

That was my first lesson in growing up as a genealogist: the records tell you what’s there, but wisdom comes from noticing what isn’t.

The 1900 U.S. Census was my teacher in this. For mothers, it included two haunting columns:

-

Mother: How many children

-

Mother: Number of living children

Seeing a line that read, for example, “How many children: 3 … Number of living children: 2” revealed so much. That quiet discrepancy was the ghost of a child missing from the record — a little one whose name wasn’t written but whose absence shaped the family.

Some birth and death certificates did the same thing, noting how many children a woman had given birth to and how many were still living at the time. Even a sibling’s birth certificate could carry the shadow of a lost child.

Today, I always document those gaps. I’ll add “Baby One” and “Baby Two” in my tree if needed, placeholders until I can find names or dates. Because every child counts, even the ones who lived only hours or days.

And in doing this work, I’ve found that my research doesn’t just grow family trees. It expands families themselves — recognizing and honoring children who might otherwise have been nothing more than a forgotten entry in a family Bible or a line in a register.

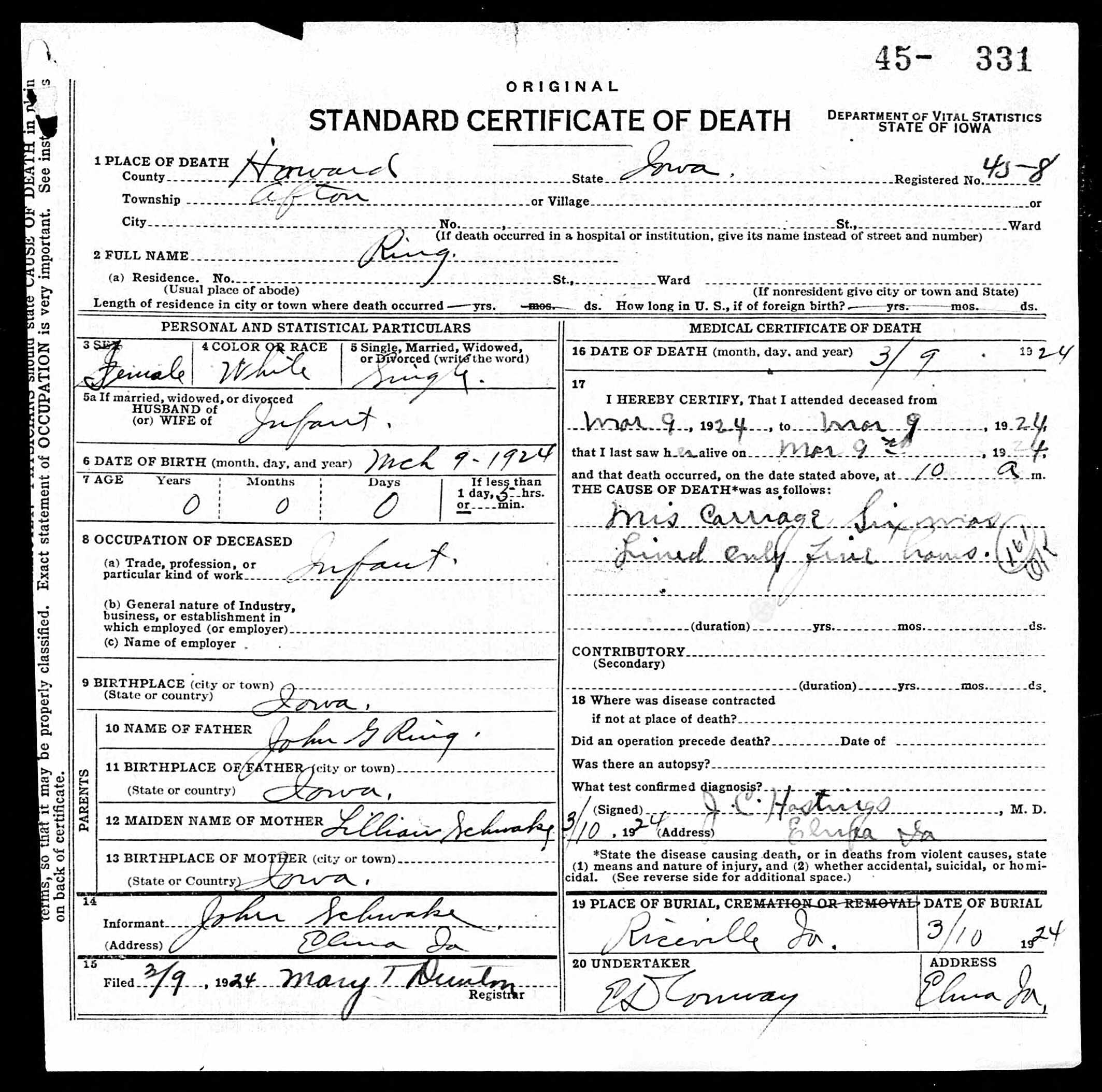

Discovering Rosella Esther

That practice led me to one of the most personal discoveries in my adopted Ring line — research I’ve done so that my siblings and cousins will have it if they ever want to know more.

I discovered my adoptive paternal grandfather’s older sister, Rosella Esther.

She was born on 9 March 1924, four months after her parents, John and Lillian, were married. She lived only five hours.

Her death certificate didn’t even record her name. It read coldly: “miscarriage, 6 months, lived only a few hours.” Officially, she was anonymous.

But her parents remembered. She was buried, her grave still marked today. And decades later, in John’s obituary, she was included: “Preceding him in death were his parents, two brothers, and a daughter.”

Even Marvin’s 1925 birth certificate carried Rosella’s shadow. Alongside his name and date, it asked Lillian to record “Number of children born to this mother” and “Number of children still living.” The answers — 2 and 1 — quietly told the story of a baby lost.

What’s striking is how that memory faded in public record. When Marvin died, his obituary listed only his father as preceding him in death — no mention of Rosella. Whether or not he and his siblings knew about her, by the next generation she was absent from the story.

That contrast — John insisting she was his daughter, Marvin remembered as the firstborn — shows how fragile memory can be in families. Rosella was both remembered and forgotten, depending on which record you read.

Lillian’s Story

Thinking of Rosella has made me see her mother, Lillian, differently too.

She was just 18 years old when she married John, who was 27. Four months later she delivered her first child prematurely, and lost her after only a few hours. Within months she was pregnant again, giving birth to Marvin in January 1925. By 19 years old, she had endured both the grief of losing a daughter and the strain of another pregnancy.

In 1924, “premature” was explanation enough. Doctors and communities didn’t dwell on a baby born too soon, and families often fell silent. But through today’s lens, I can’t help but see the weight of it on Lillian — a teenager with no chance to recover physically or emotionally before motherhood swept in again.

And yet, she carried on. She went on to raise more children through the Great Depression, through droughts and moves, through ordinary and extraordinary challenges. She quilted as her love language, and every grandchild and great-grandchild received one on marriage.

Remembering in Fabric

I only knew Lillian faintly as a child. I remember her big house on the hill, full to the brim with things - cluttered, but clearly organized. But to me, it wasn’t dirty or unpleasant. I remember her as a larger woman, always smiling, always happy. I don't know if that's the truth, but it's how I remember her.

She died in 1990 when I was 16, and I didn’t really know her. By then I believe she was in a nursing home, and in the 1980s children weren’t expected to visit those places. Looking back now, I wish I had known her more.

But years later, she reached me anyway. When I married in 1996, my grandmother — her daughter-in-law — gave me a quilt top she had found at a church sale. It had been identified as one of Lillian’s. She thought it fitting that I should have it as my wedding gift.

And in that fabric, stitched by Lillian’s own hands, I feel the continuity: the teenage mother who lost her first child, the quilter who wrapped her descendants in love, the happy woman I barely knew, and the ancestor I’ve come to know better through records and memory.

Fragments of Memory

And sometimes, the stories surface only as fragments. My adopted grandmother Berdean, now 95, recently shared a memory of her own mother talking about premature twin boys who were placed on the oven door to try to keep them warm and alive, born on the prairie of Nebraska in the early 1930s. It was a detail she had never shared before, pulled out in the middle of a conversation about family history. Hearing her describe it, I suddenly pictured her not as my grandmother but as a child, overhearing adult words, carrying them for decades. That moment was such a brain twist — realizing that the woman I’ve always known as “Grandma” still holds the perspective of a little girl.

It’s a reminder that memories change, fade, or resurface in unexpected ways — and that asking, listening, and recording is just as important as digging into records.

What We Record, What We Remember

Genealogy forces us to make choices about what to record. For me, the line is clear: any child who made it to be counted as a birth deserves a place in the tree. If they appeared on a certificate, in a burial register, or in census columns — they lived, however briefly, and they deserve to be remembered.

But some stories stay in memory rather than record. My son knows the story of how he might have been a twin, something his doctor once suggested after early complications. It’s not something I’ll ever record in a tree, but it’s a story he carries, retold to his girlfriend, part of his sense of self.

I also lost a pregnancy at 11–12 weeks. I never recorded that child in my tree, but I carry them in my heart, named and gendered in my own way. And maybe that’s where they belong — not as a line on a chart, but as a part of me.

Growing Up in Genealogy

I began my genealogy journey as a name-gatherer, writing tidy facts that sometimes stripped away humanity. With time, I’ve learned that what matters isn’t just who survived to pass on DNA. It’s also the infants buried, the mothers who quilted, the fragments remembered by 95-year-olds, and the private griefs that never made it into records.

Genealogy matures as we do. What once looked like empty census columns or missing names now reveals whole stories. And sometimes, those discoveries — like Rosella Esther, who lived only five hours — remind us that even the briefest lives deserve to be remembered.